Rachel McBride Lindsey is a scholar of religion and visual culture and teaches in the Department of Theological Studies at Saint Louis University. Lindsey's scholarship focuses on material and visual cultures of religion, particularly in relation to visual regimes of race and nation, and traverses disciplinary frameworks of visual studies, American studies, and religious studies. Her first book is A Communion of Shadows: Religion and Photography in Nineteenth-Century America (University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

This Collection was produced in collaboration with The University of North Carolina Press as an accompaniment to

A Communion of Shadows: Religion and Photography in Nineteenth-Century America, by Rachel McBride Lindsey (2017 © University of North Carolina Press).

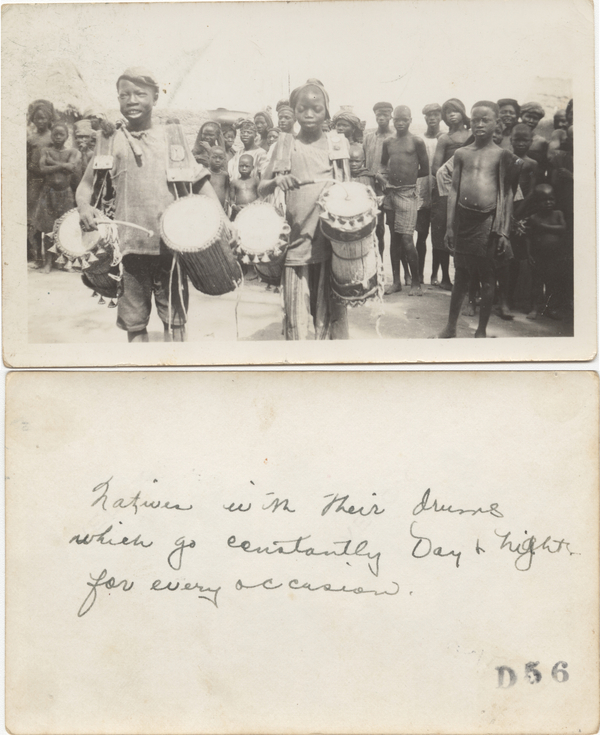

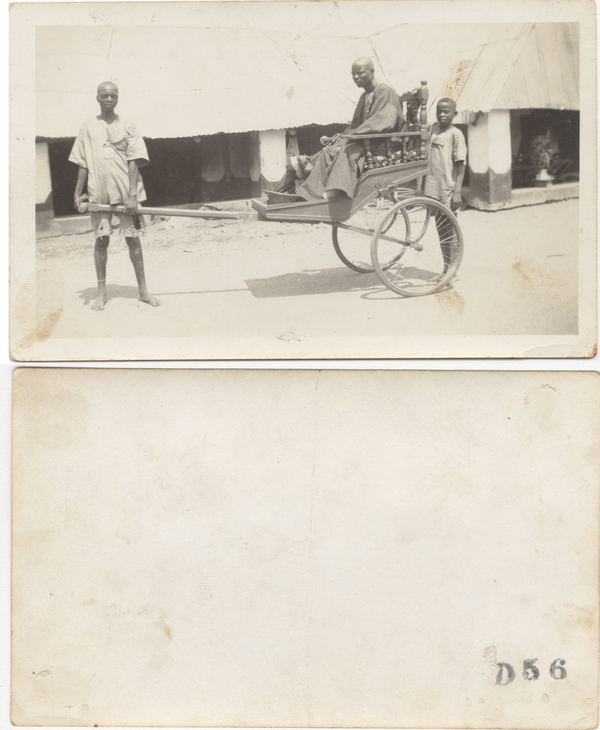

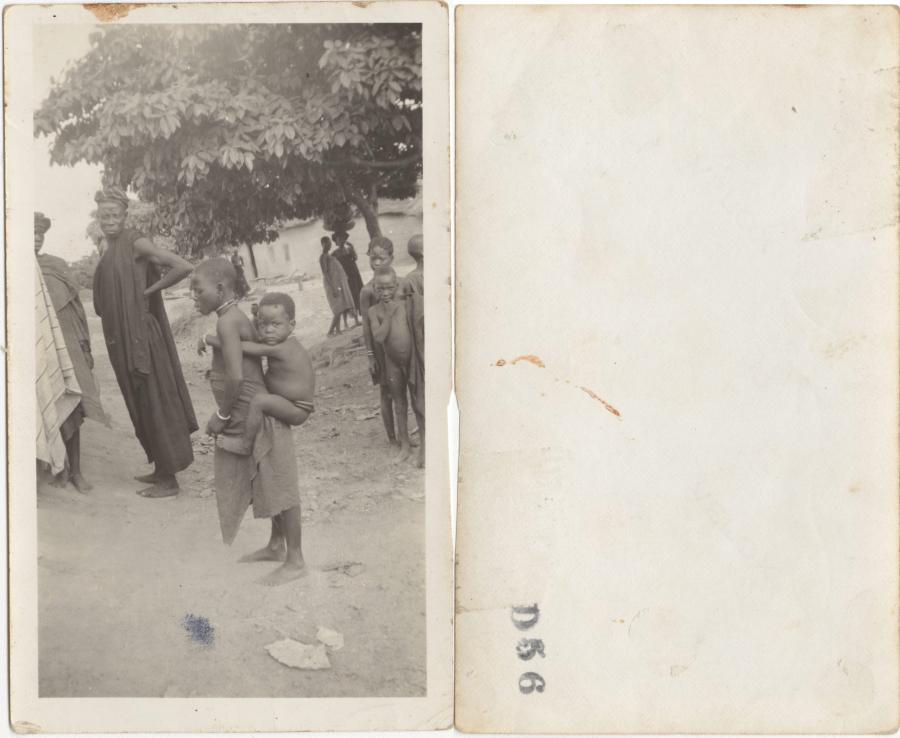

The pictures that spill out of the yellowed envelope are as perplexing as they are inviting (Figs. 1-3, 8, but see also object in gallery below for complete grouping of photographs). I first encountered these nine photographs several years ago when my great-grandmother was cleaning out her belongings before moving into assisted living. Nanny, as I knew her, was then in her nineties and would live nearly another decade. But on this day, her daughter was charged with the impossible task of separating what would survive in the family and what would, without further ceremony, be discarded. Three generations of women sat around Nanny’s living room—my great-aunt Judy on the floor surrounded by stacks of books and boxes, my grandmother Charlotte in the plaid swivel chair that my cousins and I had wickedly spun into gut-knotting dizziness against the protests of our parents, and my mother and I on the ancient orange couch redolent of girlhood visits to Nanny’s house. The small room with the picture window looking out onto the cul-de-sac encircling a single oak, whose branches had long been our hiding place and whisper tree, was now the place where we divided Nanny’s things into relics and refuse, the vessels that would carry her memory forward and the discarded stuff of the past.1

- 1

Sections of this essay are adapted from the introduction to Lindsey, A Communion of Shadows: Religion and Photography in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

Amidst letters and coffee mugs, baby pictures and tablecloths, and so many, many books, the nine 2¾ x 4½" black and white photographs from what I later learned was a hospital in Ogbomosho, Nigeria, seemed out of place. Who were these people and how did these pictures become part of Nanny’s stuff? Nanny’s family, my family, were of Scotch, Irish, German, and English ancestry, and had been in southern Missouri and what became the state of Oklahoma for generations. Our ancestors were farmers and quilters, mothers and ministers, Union soldiers and Confederate sympathizers, neighbors and, I had just recently learned, slave owners. Where did these pictures come from? What stories do they tell? Although my twenty-something self had not yet learned to scrutinize photographs with attention to the intersections of materiality and religion, I was nevertheless struck by their seeming out-of-placeness among the familiar coffee mugs, knickknacks, and Readers Digest paperbacks. I took them home, displayed them in various contexts, and eventually tucked them back into their envelope. But over time, this initial curiosity about the provenance of these pictures—where did they come from? who made them? why have they been saved?—and that of other commonplace pictures shifted into an interrogation of the cultural power of photographs as objects within economies of memory, family, and visual regimes of American Christianity.

The objects on display in this collection stitch together what I call the “communion of shadows” that began with the invention of photography in the early nineteenth century and spirals out from my book, A Communion of Shadows: Religion and Photography in Nineteenth-Century America. Rather than a history of “photography” as an abstracted, totalizing system, the book turns to the grain and heft of specific artifacts to cast light on a communion of shadows that drew nineteenth-century Americans into physical association with each other, their beloved in glory, and the biblical past through commonplace photographs. Commonplace, or vernacular, photographs are less known for their extraordinary beauty or profound content than they are experienced as ordinary, familiar, common objects in daily life. These are objects that are so familiar that we, like generations before, rarely stop to comment upon their meaning or influence—or perhaps they are so meaningful that we expect more of them than their form and depicted content seemingly convey. But when we do stop to look at rather than through vernacular photographs we begin to see the subtle but profound ways in which such objects shaped American religion almost immediately upon the invention of the new technology in the early nineteenth century. In this collection, however, I want also to sharpen the disciplinary critique that the book engages more obliquely. Namely, reflecting on the project at its conclusion, I am drawn to questions and contexts that I could not see, or at least did not recognize, at the project’s beginning—what violence do photographs do to the study of religion? Or, more cautiously, how must the academic study of religion scrutinize and transform itself in order to incorporate rigorous, sustained, and candid analyses of material and visual sources? The affirmative case for the contributions of visual and object analysis to the study of religion has been made by scholars for more than a generation, and the entirety of the MAVCOR project, among other signature journals and collections, is testament to its strength within the discipline. And yet the persistent cordoning of these methods of inquiry within scholarly communities and a seemingly consistent suspicion of said method and source bases (when I give talks about my work I almost always get asked “but what sources do you use?”) suggests that foundational, even existential, disciplinary scrutiny remains unresolved. More than navel gazing or harping from the galleries, such disciplinary attention to sources, methods, and epistemic legacies is critical to the ongoing project of defining the collective object of study.

Throughout the nineteenth century, drawing on the ritual practice and sacred symbolism of the communion table, American divines bespoke a “communion of saints” that bound the faithful on earth and in glory.1 The language was of course ancient, woven into creeds Catholic and Protestant, but the revivalism of the early nineteenth century and the palpable sectarian tension of the antebellum period imbued the sacred notion with urgent cause. Not unlike the communion of saints, the communion of shadows was a “traffic in objects” that at once bound communities into proximity with each other and generated boundaries of exclusion.2 Put bluntly, the conviction behind this project is that we do not fully know nineteenth-century American religion apart from this communion of shadows, apart from the objects themselves and the habits of beholding they conditioned. “Hand in hand,” intoned the revered African American statesman and former slave Frederick Douglass in an 1865 lecture on photography, “this picture-making power accompanies religion, supplying man with his God, peopling the silent continents of eternity with saints, angels, and fallen spirits, the blest and the blasted, making manifest the invisible, and giving form and body to all that the soul can hope and fear in life and in death.”3 This project blows the dust off of that great album of saints and angels, known to Douglass but lost to us, so that we, too, may behold nineteenth-century Americans in their work of peopling the silent continents of eternity through the new marvel of the camera.

- 1Leigh Eric Schmidt, Holy Fairs: Scotland and the Making of American Revivalism (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2001), 101–103.

- 2Elizabeth Edwards, Chris Gosden, and Ruth Bliss Phillips, Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Culture (Berg, 2006), 3.

- 3Frederick Douglass, “Pictures and Progress,” reprinted in John Stauffer, et. al., Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American (New York: Liveright, 2015), 167.

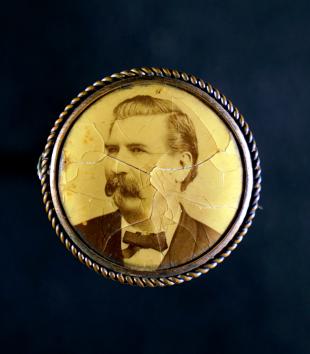

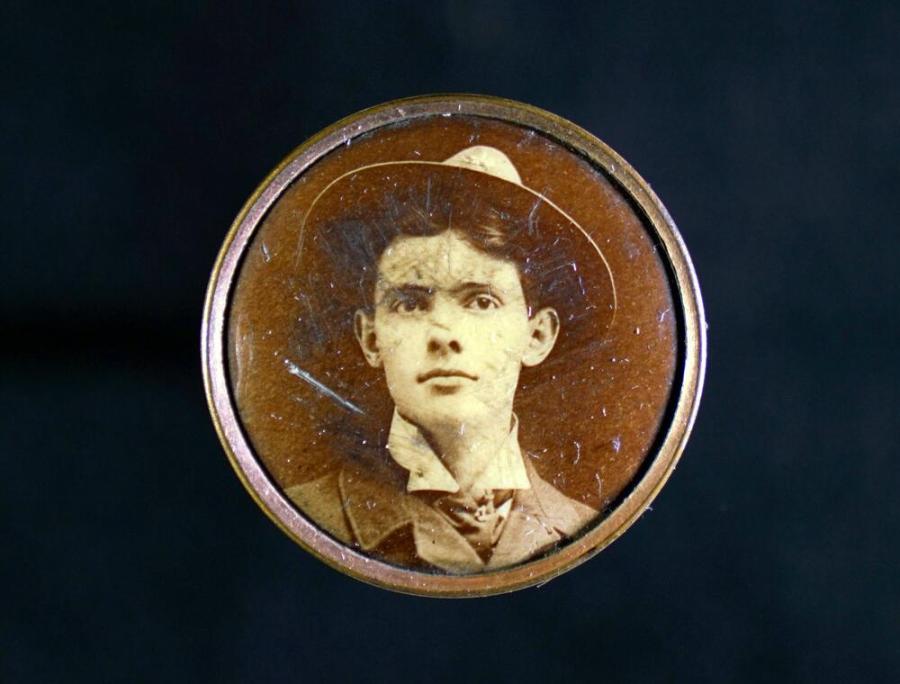

With the invention of photography, Americans inherited a new repertoire of material practice that transformed habits of perception, recognition, and representation by freighting discourses of scientific objectivity alongside artistic innovation and spiritual revelation. If religion emerged in subsequent decades as a subject in photographic trade catalogues, defined by compositional emphases on Bibles, buildings, exotic bodies, foreign vistas, and forms of attire, it was also something that was conditioned through exchanges between photographic artifacts and their beholders. Beholding is not here a synonym of mere viewing, but instead a cultural posture, and an arguably specific subjectivity, wrought from the malleable irons of perception, recognition, and imagination, and forged within the furnace of nineteenth-century visual technologies. It was, and remains, furthermore, neither analogous to nor entirely derivative of believing. Photography generated rich material archives—cameras, plates, albums, prints, viewing apparatuses, studio furnishings—that structured new religious subjectivities by mediating exchanges between these artifacts and the bodies of makers, operators, sitters, and viewers. The resulting photographs themselves, moreover, which scholars of religion have long been conditioned to encounter as images to decode or otherwise translate into visual records of historical information, were themselves material objects that freighted heft and scent and texture and temperature, that were worn on bodies, tucked into albums, and displayed on tables (see, for instance, these buttons from the early twentieth century Fig. 4-5). And finally, but no less significantly, these photographic artifacts were situated within broad inventories of optical marvels and visual media that instructed nineteenth-century Americans not only in what to see but in how to behold.

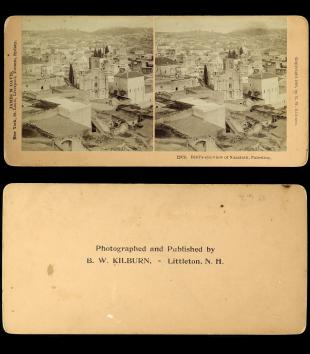

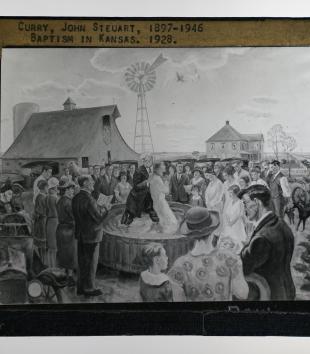

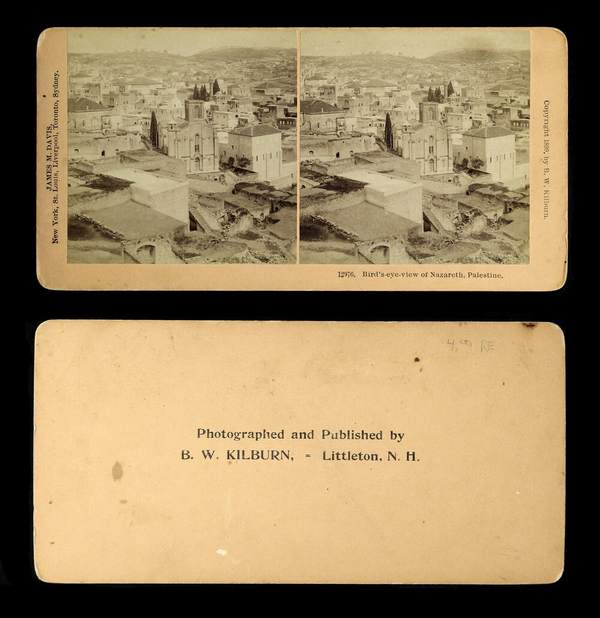

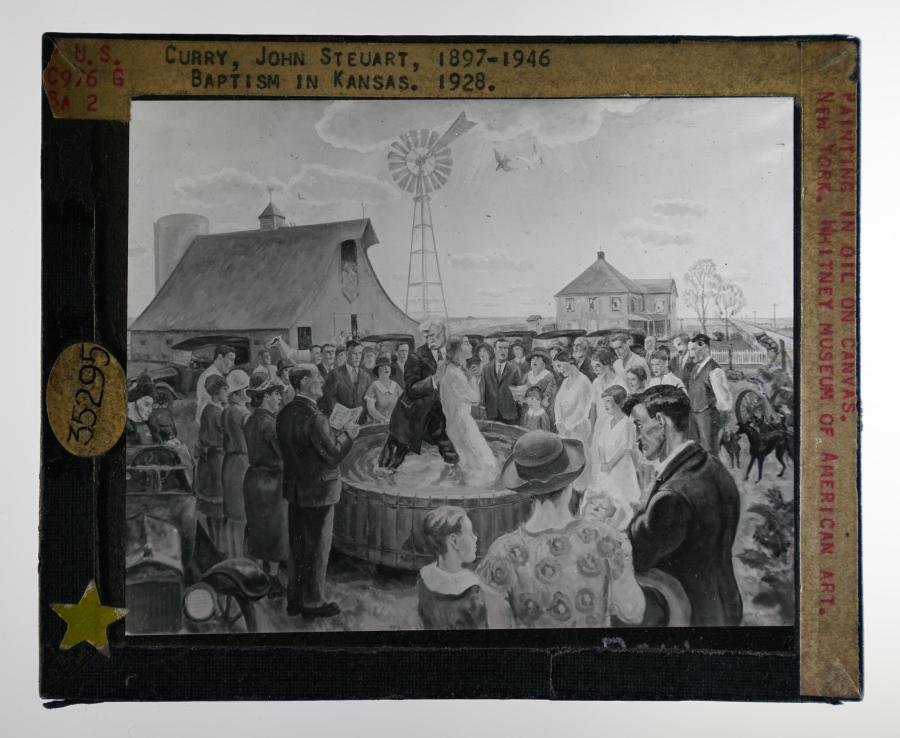

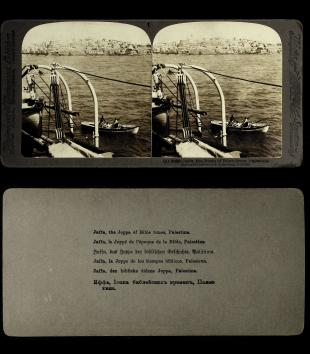

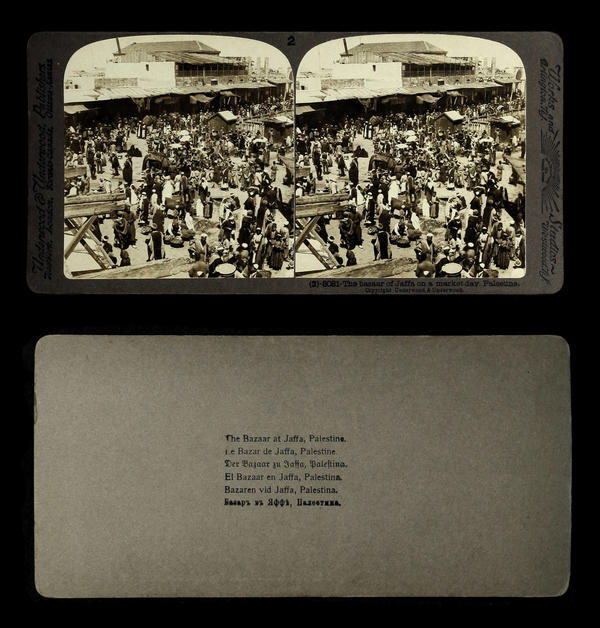

Some visual technologies of the nineteenth century underscore this point more acutely than others. Benjamin West Kilburn’s stereograph “Bird’s Eye View of Nazareth” appears to picture the ancient city from an elevated perspective (Fig. 6). In order to see what is “really there,” in the ballyhoo of the late 1890s, however, beholders fitted their faces to a contraption of metal, glass, and wood that transported them, via the wonder of imagination and optical science, to the roof of a biblical home and into the role of biblical eyewitness. Magic lanterns were another variety of nineteenth-century visual technology that instructed viewers to see in new, animated ways and, in the process, to transform their relation to self, other, and history (Fig. 7). Although much older than photography itself, by the middle of the nineteenth century magic lanterns were baptized into the church as instruments of religious instruction and personal connection with the pageantry of salvation. Between the painted canvas of the panorama and the projected moving picture of the cinema, American clergy and congregations alike began to see the world through new eyes as the magic lantern transformed, on the heels of incorporating photographic methods into the display, from an instrument of deception into one of revelation. In a word, then, nineteenth-century photographs provide not only a visual iconography of American religion but also a body of relics that, in the imaginaries of beholders, disclosed an otherwise inaccessible past into their sensorial present. Akin to Margaret Olin’s concept of “tactile looking,” in which she situates the metaphorical and metonymic operations of touch within the photographic “architecture” of the late-twentieth and early-twenty-first centuries—“a mostly paper environment made up of newspapers, flyers, posters, and screens”—the analytic of beholding is also, to use Olin’s language, “more act than reading; it produces more than it understands."1 But unlike Olin’s mostly paper environment, the objects handled in this collection do not so easily slip from haptics to metaphor. Beholding, in a word, asks us to linger a moment longer with the photograph as object. A Communion of Shadows, here and in the book, in sum, registers methodological debates in the study of material culture and visual studies, but strives to keep material and imaginative encounters between photographic objects and their historical beholders in focus.

- 1Margaret Olin, Touching Photographs, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 3, 7.

Since their emergence into the American material landscape and cultural imagination, photographs have been historical fragments perpetually seeking interpretive anchor. Here, I offer two overarching frameworks—textual cues and visual regimes—for positioning cultural analysis of photographs within the academic study of religion, a discipline that despite great strides over the last several decades nevertheless freights interpretive bias against the contributions of visual and material analysis to our common object of study. This essay and the collection of artifacts it presents can only suggest what the book aims to show through deeper engagement with vernacular photographs and their swirling constellations of objects, bodies, technologies of self and other, and economies of perception and meaning. It is also worth admitting that the very mode of communication here—digitization—and in the book—print—participates in the translation of photographic artifacts into something more akin to curated (and thus contained) visual records than to the material objects that nineteenth-century Americans experienced and beheld. Thus while this brief essay is an invitation to reconsider photography as a traffic in objects that shaped nineteenth-century American religion in profound and consequential ways—and that sheds light on disciplinary biases that have contained materiality by casting objects as at best peripheral or derivative and at worst antagonistic to the work of religious studies—it also recognizes the descriptive and analytical limitations it confronts at every twist and turn. Rather than smoothing over these imperfections and limitations, let us witness in our historical moment reflections of the processes of translation and interpretation undertaken by previous generations in their own rapidly changing technological world.

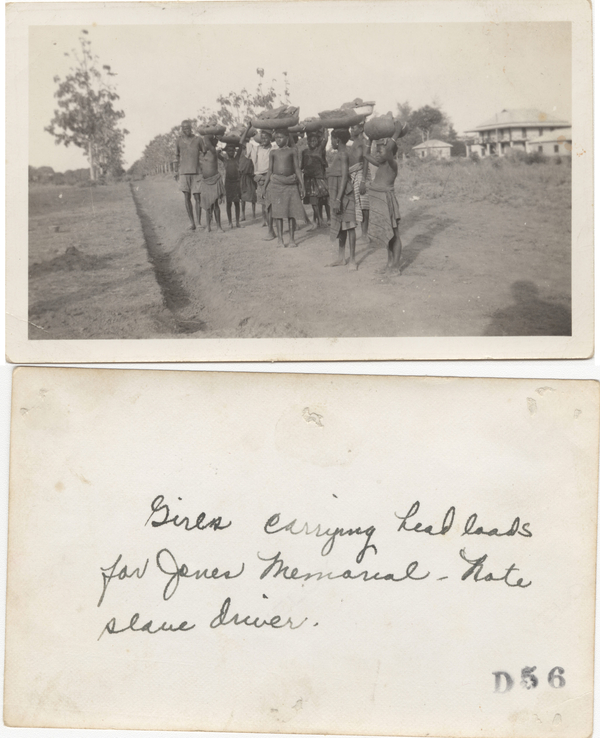

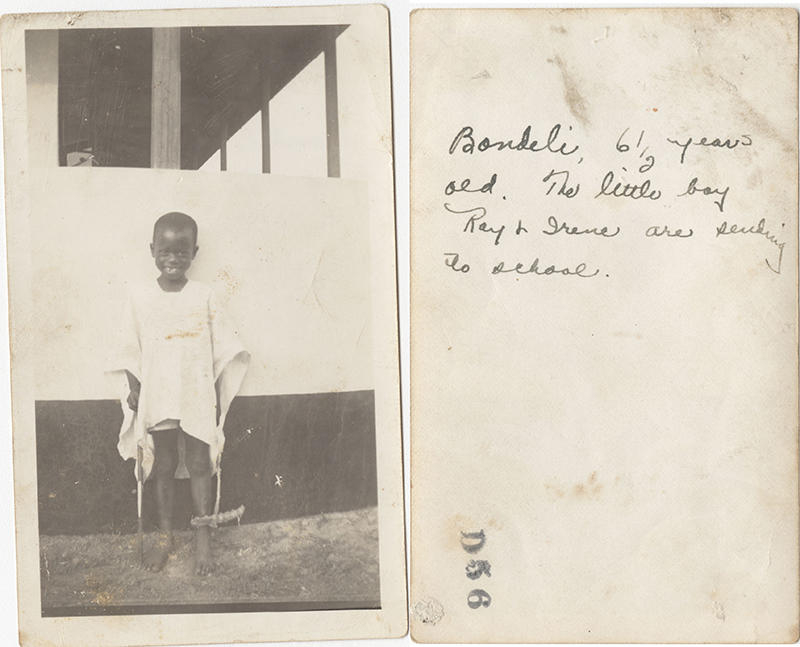

Interpretive associations between texts and images are ingrained in the history of American commonplace photography. This intersection is also a comfortable meeting place for scholars and beholders trained to trust the word as the singular bearer of history. One thread in this knotted history begins outside of the picture’s frame in the stories they invoke. Like photographs, the sonic landscapes of oral history are more often than not fragments, prompted by objects and shaped by claims to memory. In Nanny’s living room, the women remembering the pictures they now held in their hands provided only the faintest of contextual details. Ray Northrip was a missionary to Nigeria with his wife, Irene, for three years beginning in 1939 and these photographs were from that mission. Ray was a medical doctor, his white coat still stiff in its newness after graduating from the University of Oklahoma in 1938. While family memory provides some interpretive cues for the photographs, such recollections are partial and incomplete. Most glaringly, family memory speaks from the position of the white American medical missionary and is completely absent of explanation or context of the majority of the people in the photographs, the black Nigerians who found themselves one way or another—voluntarily? accidentally? subtly or explicitly coerced?—in the path of Ray’s camera. The shadow that appears in the bottom right corner of Figure 8 reminds us that every photograph in this envelope is a seam between American medical missionaries, whose narrative has been recorded and remembered in image and text, and the Nigerian patients, students, and townspeople whose stories are even more removed from the circumstances of our encounter with them. These photographs can be described with words, they can prompt stories that take on a linear progression, but these words are never the wholeness of the image.

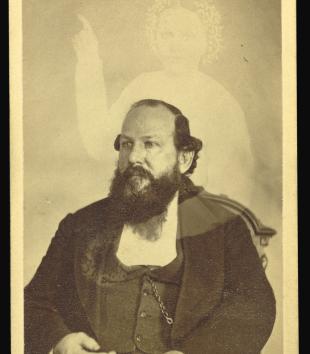

As in this example from my family’s visual-material archive, as surely as people beheld commonplace photographs throughout the nineteenth century, they also spoke about them. One vivid example of much ado about pictures was in the 1869 case of William Mumler, a spirit photographer who had been arrested on charges of fraud (Fig. 9-10, but see also the complete grouping in the object file below). In courtroom banter and witness testimony, his pictures prompted heated debate about what the camera had recorded and what his role in the process had been. Was it revelation or deception? Did his pictures prove the truth of the bible or mount an active threat to its power? During the course of the hearing, witnesses gave testimony to previous conversations they had about the photographs. Feeding a public appetite for controversy, newspaper reporters were there to record every word. In Mumler’s trial, the intersection of visual, textual, and oral histories belies scholarly compartmentalization of these methodological approaches to the study of religion.

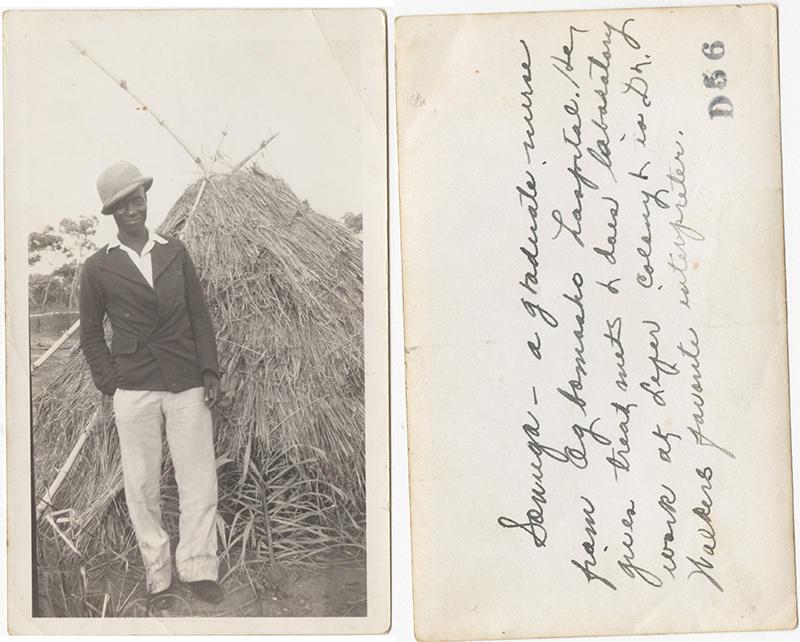

Another textual anchor is in the descriptions provided by those who have encountered the beheld photographs in the past. Someone, for instance, has written descriptions on the back of several of the Nigeria missionary pictures. We don’t know if it was Ray or Irene or some other beholder along the way. Such descriptions often provide helpful interpretive assistance through the provision of names and dates and specific locations—two examples from the envelope are “Bondeli, 6 ½ years old. The little boy Ray & Irene are sending to school” and “Sonuga—a graduate nurse from Ogbomosho hospital. He gives treatments & does laboratory work at Leper Colony & is Dr. Walkers favorite interpreter” (Figs. 11-12) These scribbles give us names. They give us knowledge. We know what to do with this information. Prior to the popularization of snapshot cameras in the first years of the twentieth century, however, such descriptions were rare and far sparser, perhaps a name or a date penciled on the back of a studio portrait, scribbled on a piece of paper that was tucked into a daguerreotype case, or inked across the surface of a landscape print.

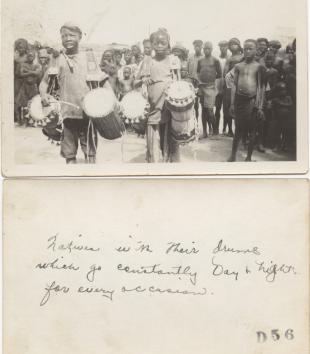

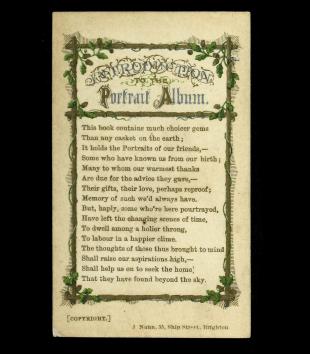

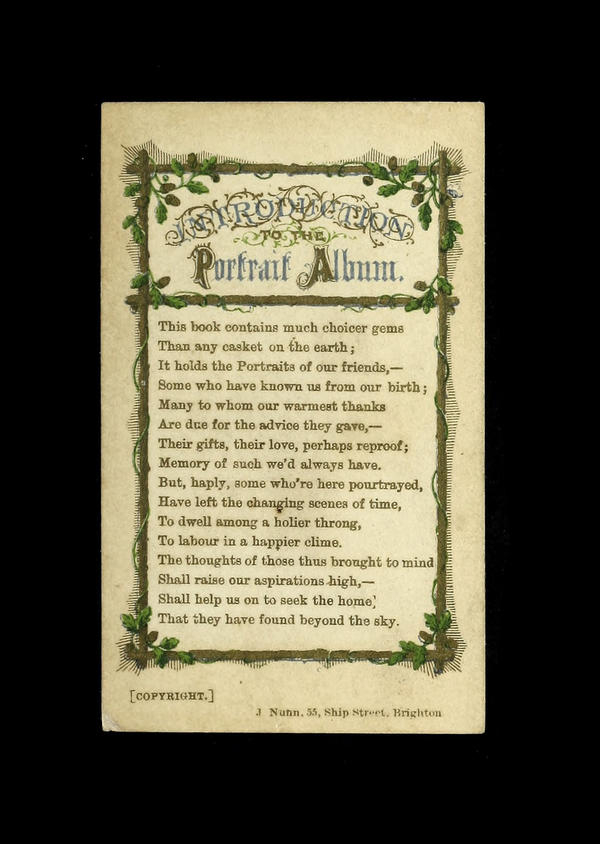

In this card-sized “introduction” to a carte de visite album (which became popular in the 1850s and 1860s), beholders are formally instructed in the marvels of the photograph through deliberate textual prompt (Fig. 13). Not only will they behold the likenesses of their friends and relations, the verse suggests, but they will also behold in these pages a seam in the fabric of time, in which the photographs stitch the frailty of the flesh with anticipated glories. But such a deliberate textual prompt was more of an exception than a rule in habits of nineteenth-century photographic beholding. More often than not, identifying markers were hidden from view by virtue of nineteenth-century display practices—portrait albums were constructed to show faces, not descriptions, and only the most intrepid of beholders would risk damaging the singular likeness of a daguerreotype by taking out the protective padding (see embedded book below). And when they do exist, such descriptions can deceive us into following certain interpretive trajectories to the neglect of others—“Natives with their drums which go continually Day & night for every occasion,” to take one example from Nanny’s pictures, freights a certain narrative trajectory to the neglect of other, perhaps more generative, directions (Fig. 1).

Perhaps the most abundant textual cue in the American communion of shadows was the Bible (see embedded books below). Within a few years of the invention of the daguerreotype, biblical archeologists and showmen were using their cameras to provide elaborately detailed illustrations in scholarship, illustrated bibles, and painted panoramas of the Holy Land. Daguerreotypes were single images on silver-plated copper and were extremely fragile. As such, they were neither capable of being reproduced in texts or of being circulated widely. Nevertheless, through translations into engravings and paintings of various kinds, daguerreotypes informed the biblical imagination of American beholders from the 1840s into the 1850s. The connection between bibles and photographs became more explicit in the 1860s when family Bible publishers began including pages for family portraits within the binding and, by the end of the century, when halftone photographic landscapes were printed in bibles themselves, thanks to the development of new technologies that enabled photographs to be printed alongside text using existing publishing apparatus. In each of these moments—daguerreotype prompts, studio portraiture in family bibles, and the introduction of so-called “photographic bibles”—the Bible not only prompted biblical beholding but, according to many ministers and commentators, was made newly legible through the camera.

Visual Regimes

Such interpretive approaches are familiar to, comforting even, to an academic discipline borne out of the regime of the word. By locating photographs within economies of text—by finding any accompanying scribbles or print—photographs become legible within existing hermeneutics of religion. As Birgit Meyer and others have convincingly shown us, the academic study of religion was and in many ways remains the heir of colonialist regimes designed to contain and control competing claims to material and spiritual power in the modern period. Integral to this strategy of knowledge-production was epistemic iconoclasm, increasingly shadowy as overt religious claims were swallowed by discourses of cultural and intellectual objectivity. A Communion of Shadows, among other recent work in the field of material studies of religion, asks us to consider disciplinary biases that wield the text to control the image, and in turn to begin to behold as well as to know. In short, we know photographs through the words they prompt from makers and beholders—a communion in which we too are conscripted—but we also, and just as acutely, behold them through the wordless stories they conjure and convey behind, through, and across limits of language. The theorist Roland Barthes called the affective response to a photograph the “punctum.” For Barthes, the punctum is not a fixed element of the composition but is instead the compositional accident—a facial expression, a passerby, a shadow—“that pricks, bruises me.” If the studium, his dialectical construction to the punctum, allows “discovery of the operator,” the punctum gestures to the beholder by revealing the juncture of histories that burst into a moment of encounter. Barthes was a cultural critic steeped in the power of language, but his notion of the punctum defies linguistic capture. It is neither literary trope nor visual representation. It is less of the order of place than of the order of time. It is a moment of conjure that is beheld and experienced more than it is known. It is precisely the kind of uncontained disorder that the discipline of religion was created to control through mechanisms of the word. Turning to photographs as photographs—not as visual affirmations of knowledge derived from texts—invites us to reconsider the very contours of the discipline and to advance more rigorous analytics that are attentive to multiple registers of religious and theological experience.

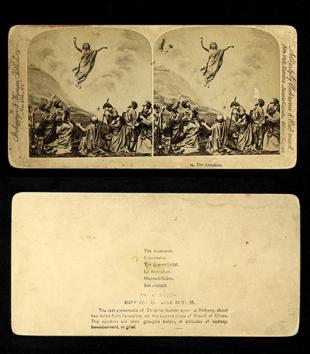

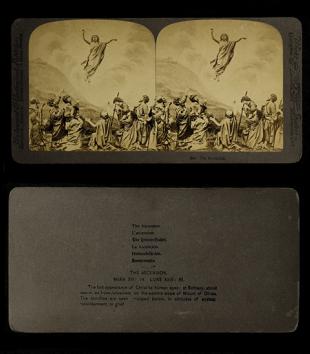

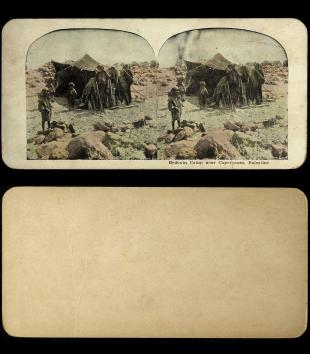

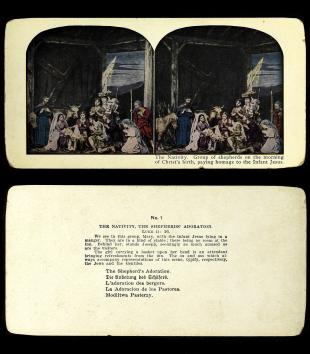

It is tempting to romanticize the beholder’s affective response as dramatically individualized. But beholding is always a historical act shaped by an unspoken tangle of practices of display, reception, and recognition—something we might describe as a visual regime or, from a different perspective, a politics of beholding. In stereograph series of Jerusalem and Palestine at the turn of the twentieth century, for instance, many beholders saw not a photographic contemporary but a biblical past. They, in short, looked beyond the surface of the photograph to see, in their own estimations, what was really there. Stereography preceded the invention of photography by several years, but with the advent of print techniques in the 1860s photographic stereographs became a popular form of mass culture. Various narrative strategies were adopted over the latter decades of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth that aimed to recreate biblical narrative through visual experience and haptic association. From bootlegged staged French series of the life of Christ to high-quality original stereographic images to, in turn, cheap chromolithographic reproductions of American originals, the market in stereographs of biblical and religious themes was vast and deep. Shaped by technologies, markets, and practices of display, as well as more diffuse systems of knowledge informed by visual regimes of race and empire, when beholding series in Palestine, many viewers claimed that, through the wondrous technology of the stereoscope, they in truth beheld biblical landscape and biblical actors instead of their photographic contemporaries. In such claims we begin to see the subtle but pervasive ways in which photographs, as well as images of other kinds, created rather than corroborated biblical knowledge among nineteenth-century beholders.

Attention to the visual histories and visual claims of photographic media helps us to discover the beholder, or at least to discover the beholder’s shadow, by prompting different analytical trajectories from those of conventional disciplinary approaches. Instead of lingering on functional analyses of what photographs mean within existing paradigms of classification and analysis, for instance, we begin to inquire about the structural and technological contexts that put a camera in the hand of white missionaries from Oklahoma who found themselves in Nigeria in the fall of 1939: What visual habits informed the capture of the snapshot and the reception of the image by various beholders? How did the camera become a technology of American missionary activity? Are there connections between the camera as a technology of the state and a technology of the soul? If so, what are the specific nodes that bring these fields into association? As with all anchors, neither of these approaches is final—they are portable, if not entirely nimble. Indeed, they are made to move as well as momentarily to fasten. From the surface, the nine snapshots in Nanny’s collection are perhaps little more than banal curiosities and detached fragments. Below the surface, however, they invoke reciprocal worlds of production, recognition, reception, and display that have animated American religious experience and imagination for nearly two centuries.

Notes

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/mav.coll.2017.1

1. Rachel McBride Lindsey, “A Communion of Shadows: Religion and Photography in Nineteenth-Century America,” Collection, in MAVCOR Journal 1 (2017), doi:10.22332/mav.coll.2017.1

Lindsey, Rachel McBride. “A Communion of Shadows: Religion and Photography in Nineteenth-Century America.” Collection. In MAVCOR Journal 1 (2017), doi:10.22332/mav.coll.2017.1