An exhibition curated by:

Kati Curts, Olivia Hillmer, and Michelle Morgan

Graduate Affiliates of the Center (formerly Initiative) for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion

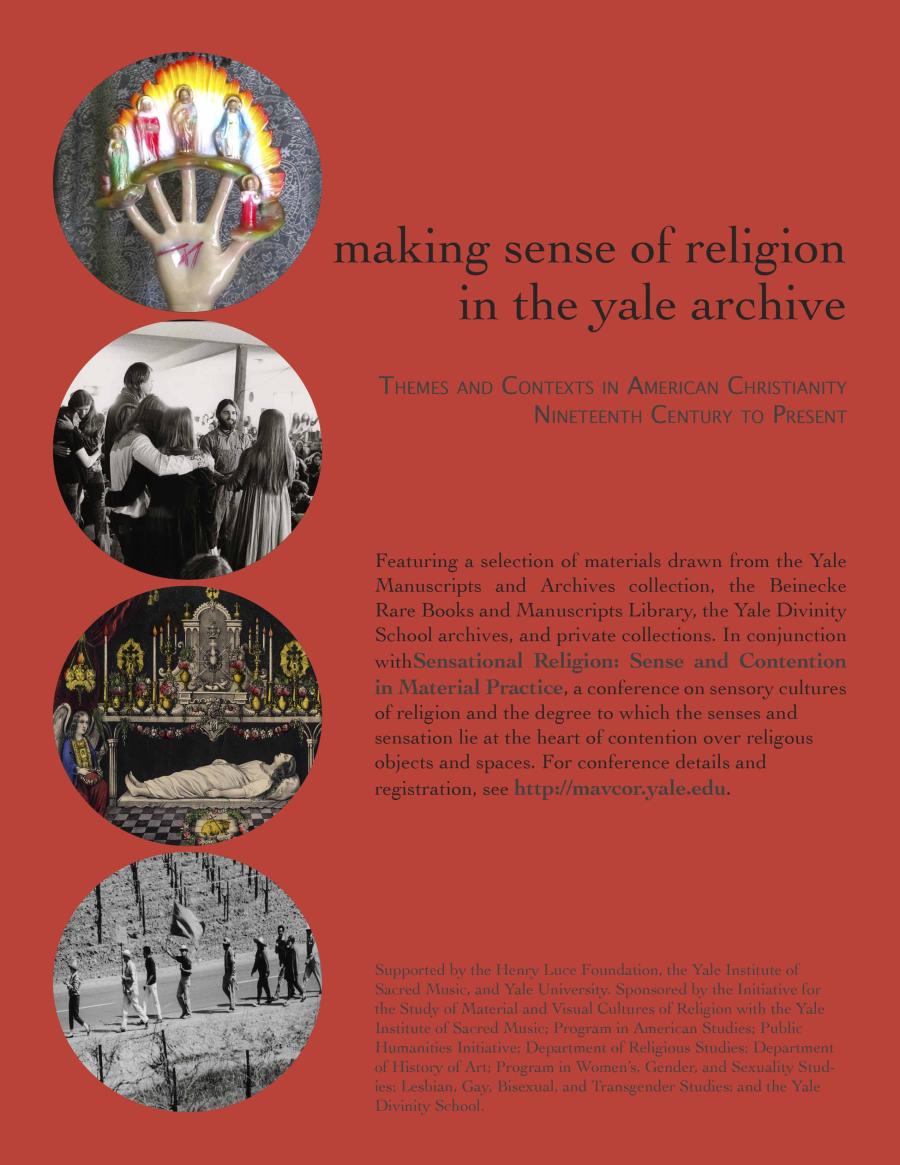

Religious images, objects, spaces, and performances are constituted by and reflective of a dynamic human sensorium of taste, touch, sound, scent, and sight. Indeed, the sensational human body is the medium through which religious practitioners encounter pleasure and pain, ecstasy and sacrifice. Individuals and groups also work—through and with sensory perceptions—to discipline their own and other bodies in religious ritual, performance, and play. The entangled issues of gender, sexuality, race, technology, nationality, foreignness, and perceptions of progress result in similar sensory encounters with objects eliciting different responses from different audiences.

Making Sense of Religion in the Yale Archive emerged from the intersection of two deceptively simple questions: How do individuals make sense of religion, and how does religion make sense? Engaging the rich diversity of meanings evoked by the word “sense” invites examination of relations among religious sensibilities, sensing and sensual bodies, and sensationalized religious spectacle. The materials exhibited here, drawn from the Yale Manuscripts and Archives collection, the Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscripts Library, the Yale Divinity School Archives, the Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library, and private collections, provoke questions about scholarly ways of understanding and interrogating sensory cultures of religion. These materials also ask how notions of the sensational form and inform histories of religion, religious actors, and events.

Each of the objects, photographs, texts, and ephemera selected here has its own subjects, each its own ways of evoking sensation. Importantly, from a curatorial perspective, each also has a history of human use. Well before individuals collected and sequestered these things in library shelves, people (possibly including the collectors themselves) created, possessed, and used the objects that fill these cases. Some uses distanced the objects from human touch and sensory engagement, whether or not the object itself invited interaction. Now conservation, glass cases, careful lighting, and spatial distance prevent the hands-on interaction some of these objects originally received. Some items—for better viewing, to protect against fading, or because of an object’s fragility from years of wear—are displayed as reproductions of what is actually archived in the collection. Archival and curatorial practice, while preserving the objects, now restricts sensory circulation of the objects--which nonetheless invite and focus attention and sensation in various ways for various audiences. In addition, the kinds of objects collected by curators are often less rich in sensory data, though they might remind one of or suggest a sensory experience. Objects, such as paper items, or objects about objects, such as drawings of religious implements, lend themselves to simple conservation and storage, but are also less likely to express the sensory qualities so crucial and evocative to religious practice. As you encounter this exhibition, we curators invite you to remain aware of the attention you pay to certain objects, which attract you and which you must work to appreciate, and consider how the ease or difficulty of sensing affects what you learn from or enjoy about each object.

Exhibition Checklist

Theme I: Making Sense of Religious Vision

Western hierarchies of the senses have long granted vision the privileged position, followed, typically, by hearing, touch, taste, and smell. Though vision undoubtedly plays a critical role, its monopoly on the study of religious experience has perpetuated particular, limited understandings of religious belief and practice.

The idea of religious “vision” itself offers a range of possible interpretations and meanings: It refers to “sight” of an ecstatic sort that has inspired belief for some religious and spiritual systems but it calls to mind multi-sensory experiences beyond the strictly visual. “Vision” also invokes the sense of visualizing religion’s future—of the strategic ways various religious denominations perpetuate their projects, agendas, and communities through sensory means. For any of these interpretations, it is important to consider perspective and point of view, to imagine whose vision frames particular understandings of what it means to be religious in the first place.

The objects in this section of the exhibition each take up the question of religious vision, particularly as vision acts as a point of perspective—a framing device that has set the terms of inclusion and engagement. Religious vision is posited here not to reify or protect its privilege but as a point of departure for encounter with various sensory formulations that comprise religious experience while holding in play, simultaneously, the idea that particular and often hegemonic perspectives frame what religion “looks like.” The items on display here invite the visitor to reimagine the various ways religion “makes sense.”

(Case 1a) – NO ITEMS, TEXT ONLY

(Case 1b)

(1)

Advertisement. “Don’t Believe Everything You See? Try The Skeptical Inquirer.” Gambler’s Book Club, vol. 3, no. 2, ca. 1970. Brand Blanshard Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(2)

News article. David W. Hacker, “Humanists Take Aim at Modern ‘Gullibility.’ Panel would Exorcise ‘Mysticism.’” The National Observer, May 15, 1976. Brand Blanshard Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(3)

Lantern slide. Graveyard scene, n.d. For use in educational programs about the theater. Crawford Theater Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(4)

Engraving. William Blake, “The Soul Exploring the Recesses of the Grave,” (engraved by A.L. Dick), 1847. Salisbury Family Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(5)

Lithographic print. Nathaniel Whittock, “Panoramic View of Jerusalem and the Adjacent Towns and Villages,” Published London, 1842. Salisbury Family Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(6)

Ticket. “Ramparts Walk: Jerusalem Old City Walls,” 1986. Christopher Phillips Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(7)

Painted cast metal statue. “Black Madonna” of Hal, first quarter of 20th century. The “Black Madonna” of Hal’s skin color is produced from the ash generated from cannon fire; notice that she stands atop cannon balls. Private Collection.

(8)

Chalkware statue. St. Lucy, Columbia Statuary 124, ca. 1950. Private Collection.

Theme II: Making Sense of the Sensationalized

Missionary tracts and playbills, scrapbooks and souvenir books frequently sensationalize religion, presenting ritual or devotional practice in the form of spectacular scenes--and scenery. The importance of the sensory and sensual regularly takes center stage in theatrical productions and news stories, in sites of international exhibition and entertainment, and in guides to right practice, belief, and discipline. Scenes of religious experience, in other words, become sensationalized through the workings of the senses.

In the context of this archival exhibition, religion’s performative and theatrical elements invite questions about how these aspects of practice express and construct meaning. As bodies—personal and institutional—engage religion, these human subjects often construe sensory perception as a gateway to experiential knowledge, reproducing particular religious sensibilities and eschewing or occluding others. Scholars and practitioners frequently rank sensory perceptions, with some sensations deemed more valuable and appropriate than others. Deliberate emphasis on non-visual sensory perception, especially, can—and often does—arouse controversy and conflict.

The objects and images in these cases attest to the power of the sensationalized religious performance on the stage and in the press. Sarah Bernhardt played numerous “religious” figures, highlighting the contrast between her performance of pious religiosity onstage to her sensationalized off-stage persona. Prints depicting the sights, sounds, tastes, and touches of “Broadway on Sunday,” for example, demonstrate the degree to which theater itself was sensationalized. And Henry Ward Beecher—the most well known nineteenth-century preacher—was the subject of countless sensationalized news stories when he was accused and tried on charges of infidelity. His handkerchiefs, presumably soiled with his tears, sweat, and nasal fluids, take on the aura of sensationalized relics in these archival collections.

(Case 2a)

(1)

Play synopsis. Le Proces de Jeanne d’Arc (The Trial of Joan of Arc). Starring Sarah Bernhardt. Written by Emile Moreau. Published by Fred Rullman, New York, 1910-1911. American Life Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(3)

Temperance tract. “Argument Against the Manufacture of Ardent Spirits. Addressed to the Distiller and the Furnisher of the Materials.” By Edward Hitchcock. American Tract Society, No. 242, n.d. Beecher Family Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(4)

Scrapbook album of theater buildings. Prints from Harper’s Magazine, "A Broadway Sunday Sacred Concert in New York,” October 8, 1859 and “A German Beer Garden in N.Y. City on Sunday Eve,” October 15, 1859, by A. Fredericks. Crawford Theater Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(Case 2b)

(2)

Scrapbook album. Sarah Berhardt as the Sorceress in Victorien Sardou’s, The Sorceress, 1903. In Sardou’s drama, Bernhardt’s character, Zoraya, cures with hypnotic powers and is burned on a pyre. In his foreword to his 1917 English translation of the play, Charles A. Weissert remarked of Sardou’s technique: “This is not ordinary stagecraft—it is the necromancy of stagecraft!” Crawford Theater Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(5)

Periodical. “Jesus Christ Superstar,” The Catacomb Press, n.d. (ca. 1970s). Published by Evangelist Clinton White, Lancaster, New Hampshire. Movement (Protest) Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(Case 2c)

(6)

Newspaper article. “A Human Salamander. Youth Bathes in Flames and is Unhurt.” Unknown newspaper, December 21, 1908. John Ferguson Weir Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(7)

Newspaper article. “Possessor of Second Sight, Supposed to be Alive—” New York Tribune, June 22, 1902. Summarizes Mollie Fancher’s physical ailments and “gift of second sight.” Doctors, including George Beard, also examined the woman’s ability to live on small amounts of food. George M. Beard Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(14)

Souvenir book and photograph (reproduction). 1893 Chicago World’s Fair Art Portfolio Series. “A Participant in the ‘Danse du Ventre,” Dream City Book. Beautiful Scenes of the White City. A Portfolio of Original Copper-Plate Half-Tones of the World’s Fair. Its Marvelous Architectural Groups, Statuary, Interiors, Lagoons, and Vivid Scenes from the Famous Midway Plaissance, part I, vol. 1, no. 1. Feb. 12, 1894. Published by Laird & Lee, Chicago. Exhibitions Collections, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(15)

Frontispiece and title page (reproduction). From Mollie Fancher, The Brooklyn Enigma. An Authentic Statement of Facts in the Life of Mary J. Fancher, The Psychological Marvel of the Nineteenth Century. Unimpeachable Testimony of Many Witnesses. By Abram H. Dailey. Published by Eagle Book Printing Department, Brooklyn, New York, 1894. Nineteenth Century Special Collections, Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library.

(Case 2d)

(8)

Dried flowers. From those laid upon Henry Ward Beecher’s coffin at his funeral, March 11, 1887. Beecher Family Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(9)

Scrapbook. “The Room in which Mr. Beecher Died” and “The Funeral Rites of Henry Ward Beecher—Lying in State in Plymouth Church.” Clippings from unidentified sources, n.d. (ca. 1887). Beecher Family Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(10)

Handkerchiefs and scarf of Henry Ward Beecher. Beecher Family Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(12)

Newspaper clipping. “How to Make Pastoral Visits and Avoid Slander,” The Daily Graphic, Sept. 14, 1874. Beecher Family Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(Case 2e)

(11)

Pamphlet. “Spiritualism and Free-loveism.” The Veil Removed; Or, H.W. Beecher’s Trial and Acquittal Investigated. Love Demonstrated in Plain Dealing. Published by “A Class-mate of H.W. Beecher.” New York, 1874. Beecher Family Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(16)

Newspaper. “A Few Points in Bessie Turner’s Evidence” and “Ashes to Ashes—A Plan for Cremation in Gas Retorts” The Daily Graphic, no. 637, March 25, 1875. The latter provides a plan for a crematorium designed by E.H. Clarke, which would reportedly be “of excellent service in burning the bodies of all the folks intimately connected with the Beecher-Tilton affair.” Beecher Family Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

Theme III: Making Sense of a Gendered Religious Sensorium

Within the Western hierarchy of the five senses, vision is often considered the “highest” sense. Along with hearing, it is also often associated with the rational, disembodied, “male” mind. Because the senses of smell, taste, and touch are associated with intuitive sensing rather than ostensibly objective empiricism, they have been considered “female,” as well as “lower,” senses. This gendered categorization of the senses permeates all aspects of daily life, including the religious.

Some objects demonstrate how the “lower” senses have been deployed within a female-gendered religious practice. Traditionally female domestic realms--the hearth, the kitchen, cooking--engage the senses of taste, touch, and smell, as recipe books show. A needlepoint sampler and its careful, touch-centric finger work here expresses the equally sensory experience of heat, imaginatively felt through the depicted image of the flaming heart.

Looking more carefully, however, this male-female binary is disrupted, as religious experience through the senses is hardly a strictly female affair, nor is detached, disembodied vision strictly male (nor is vision necessarily detached or disembodied). The nineteenth-century photo album and scrapbooks—signposts of the domestic realm—rely on visual iconography; in one particular iteration the physicality of the body is gendered male as young men work their limbs during turn-of-the-century calls for muscular Christianity. The photograph of a family group gathering around an organ in a parlor setting juxtaposed alongside the group of songs for “Men” invite reflection on possible constructed relationships between hearing and gender. Objects intended for the Roman Catholic observance of last rites and communion keepsake boxes engaged women primarily as consumer, relying on male priests to enact these rites. The objects nonetheless largely contained the same materials and were used to mark and enable life transitions regardless of gender.

(Case 3a)

(2)

Song Book. Men’s Songs. Adapted and used by the National Federation of Men’s Bible Classes, 1947. Donald MacInnis Papers, Special Collections, Yale University Divinity School Library.

(1)

Recipe book. Cullinary Cullings. Being Tried and True Recipes, Carefully Collected. Published for the “Ladies Fair” and the Building Fund of the YMCA in Newburgh, NY. Published by Journal Printing House and Book-Bindery, 1883. Darrach Family Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(3)

Scrapbook album of student days at Colgate University. Colgate, YMCA “In the Gym” announcement card, ca. 1893. Morse Family Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(4)

Needlepoint. “Endure the Cross.” Date unknown (mid-late 19th century). Robbins Family Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(Case 3b)

(5)

Photograph album. In addition to family portraits and collected ephemera, the album includes photographs of patients and staff from New York Hospital where Helena Darrach’s husband, James Darrach, served as superintendent. Pictured left to right, top to bottom: Israel [?]; [Aunty?], Nurse in N.Y. Hospital; [?] White; “Moses Receiving the Tables of the Law,” ephemera used to decorate a Christmas tree, ca. 1863. Darrach Family Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(6)

Last Rites Box. 20th century. Private Collection.

(7)

Photograph. Avery Family, Chicago, Illinois, ca. late 19th century. Todd-Bingham Picture Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(8)

Periodical. “Lesson VII: The Timid Woman’s Touch,” The Pilgrim Quarterly (Congregational), 1889. Todd-Bingham Memorabilia Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(CASE 3c)

(9)

Instructional pamphlet. “The Art of Making Altar Linens,” Order of St. Veronica, Huntington, Indiana, ca. 1930. Private Collection.

(10)

Boy’s First Holy Communion Remembrance Box. Edward O’Toole Company, given to Edward Perri, 1935. Private Collection.

(11)

Girl’s First Holy Communion Remembrance Box. Given to Neelan Giaquinta, ca. 1936. Private Collection.

(12)

Photograph. First Holy Communion (with little sister in angel costume), ca. 1950. Private Collection.

(13)

Photograph. First Holy Communion, ca. 1930. Private Collection.

(14)

Chromolithograph for scrapbook. Rock of Ages, ca. late 19th century. Private Collection.

(15)

Scrapbook of Harriet W. (Smith) Hawkes, ca. late 19th century. Private Collection.

Theme IV: Making Sense of Extreme Pain and Pleasure, Sacrifice and Sex

Distinguishing the purportedly extreme in sensory experience is no simple or uncontested task. When related to erotic pleasure and suffering, in particular, such distinctions evade neat categorization and invite analyses of the stakes involved in the designation of acceptable encounters. Religious institutions and traditions have helped constitute and control these extremes by limiting their occurrence, managing allowable experiences, and sometimes entirely inhibiting those behaviors they wish to discourage or prohibit. The objects in this case focus attention on some ways Christianity has approached such concerns.

Consider acts of sacrifice and extreme suffering. From the crucifixion of Jesus to ascetic self-harm to religiously motivated war, individuals and groups frame and mediate suffering through categories of virtue, justice, righteousness---and their presumed opposites. In many cases, suffering and pain have been cast as positive experiences, connecting the observant sufferer with the model of Jesus or providing opportunities for expiation of transgression. By contrast, pleasure, and especially embodied sexual pleasure and eroticism, have sometimes been repressed or perceived as a vice. The range of Christian perspectives on sexuality becomes even more complicated with respect to human reproduction where the (painful) effort of giving birth is variously presented as blessing as well as curse. These judgments of pain and pleasure call into question the individuals making said judgments, and whose bodies and experiences they take into consideration.

Further, on the postcard depicting a feminine body’s passionate embrace of the cross such a concern for surplus bodily expression gets reframed and repositioned. Likewise, the surprising mixture of sensual imagery and practical information in the birth control pamphlet, and the intermingling of religious discipline and sexual eroticism in Maria Monk’s novel, The Nun, raise similar questions in the context of this exhibition. These objects, and others in this section, showcase the many ways people struggle to negotiate lived desires and everyday encounters—both pleasurable and painful—with ideals and orders that might otherwise foreclose or contradict these experiences.

(Case 4a)

(1)

Poem. “You stood erect and fresh,” by Frank Colapinto, ca. 1963. Christopher Phillips Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(2)

Pamphlet. “Love: How to Obtain It and How to Retain It,” author and date unknown. Todd-Bingham Memorial Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(3 & 4)

Handbook. “Rhythm” and “Abortion,” Birth Control Handbook. Ed. Donna Cherniak and Allan Feingold. Photography by André and Danielle Giguère. 6th Edition, March 1971. Produced by Journal Offset, Inc. Montréal, Québec. Movement (Protest) Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(5)

Novel. Maria Monk, Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk (London, mid-nineteenth century). Private Collection.

(Case 4b)

(6)

Periodical. Illustration of scourges, The Sunday School Quarterly, 1888. Todd-Bingham Memorabilia Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(7)

Postcard. Woman draped on cross, Raphael Tuck and Sons, Easter Post Card Series, ca. 1908. Private Collection.

(8)

Postcard. Woman draped on cross, Raphael Tuck and Sons, Easter Post Card Series, ca. 1908. Private Collection.

(9)

Brass medal. From Army and Navy Commission of Protestant Episcopal Church, 1941-1945. Verso reads: “Presented to … in recognition of his service as chaplain in the armed forces in WWII by the Army and Navy commission of the Protestant Episcopal Church on behalf of a grateful church, 1941-1945.” Sherrill Family Papers, Special Collections, Yale University Divinity School Library.

(10)

Brass medal. Awarded to chaplains of American Army and Navy, 1917-1918. Sherrill Family Papers, Special Collections, Yale University Divinity School Library.

(11)

Pamphlet. “Aids to Prayer,” published by Laymen's Missionary Movement, n.d. Donald MacInnis Papers, Special Collections, Yale University Divinity School Library.

(12)

Hand-colored steel engraving, book illustration. Judith. Second half of 19th century. This illustration came from a volume of Appleton’s Women of Israel, which underwent numerous printings. Private Collection.

(13)

Hand-colored steel engraving, book illustration. Esther. Second half of 19th century. This illustration came from a volume of Appleton’s Women of Israel, which underwent numerous printings. Private Collection.

(14)

Cast metal crucifixion with instruments of the Passion of Christ. Late 19th century. Private Collection.

Theme V: Making Sense of Religious Stuff

The stuff of religion mediates and interferes with how actors taste, touch, smell, see, and hear or sound religion. Things function as religious props, where the word “prop” is also, interestingly, shorthand for property (which can, in turn, refer to “qualities” or “possessions”). Religious objects are often purposely constructed and operate as materialized access points for largely immaterial forces. Accepting the ambiguity of an object’s capacity to prop up sensory perception does not necessarily occlude its ability to signify religiously. Props can function as both aids to religious practice and as the remnants of it---but religious stuff makes sense in other ways as well.

The fabrication of these props can take on religious meaning, entangling the lives of religious practitioners and their items and implements. Religious objects created by hand might provide a particular meaningful connection between creator and user. The Industrial Revolution and introduction of mass production further complicated the interaction of objects and people. Henry Ford, for example, referred to “machines” as “ministers to man.” Such machines quickly produced items designed for a kind of sensory intimacy, to be worn close to the body, delicately handled by cautious fingers, or carefully selected among pages or shelves of varied products.

In many cases, the sense of touch is compounded by other senses, like the scent of the Tulsi, or holy basil, used to make a string of beads, or a rosary made from rose petals. These religious artifacts marked important events, facilitated essential practices, and divined messages from the beyond.

(Case 5a)

(1)

Booklet. “Bible Readings and Prayers. For private use, or for use by Bible or Study Classes, or at Meetings.” Nation-Wide Campaign, no. 2028. Published for use by laity of the Episcopal Church and Anglican Communion. n.d. Evarts Family Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(2)

Yad. Jewish pointer for reading sacred scrolls, 2011. Private Collection.

(3)

Trade magazine and promotional material. “Sing a Song of Gift Lists,” Steel Horizons, vol. 1, no. 5., 1939. Published by Allegheny Ludlum Steel Corporation, Pittsburgh, PA. Distributed at New York World’s Fair, 1939-1940. Century of Progress World’s Fair Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(4)

Newspaper article. “Machines as Ministers to Man,” by Henry Ford. New York Times, World’s Fair Section, March 5, 1939. Century of Progress World’s Fair Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(5)

Souvenir book. “Communion-Table, from Boston.” Gems of the Centennial Exhibition: Consisting of Illustrated Descriptions of Objects of an Artistic Character, in the Exhibits of The United States, Great Britain, France, Spain, Italy, Germany, Belgium, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Hungary, Russia, Japan, China, Egypt, Turkey, India, Etc. Etc., at the Philadelphia International Exhibition of 1876. Published by D. Appleton & Company, New York, 1877. Exhibitions Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(Case 5b)

(6)

Tulsi (Holy Basil) Necklace. Gift from Ghandi to the wife of Vijayaben M. Pancholi, a member of Ghandi’s ashram, ca. 1935-1948. Pancholi Collection, Sterling Memorial Library, Manuscripts and Archives.

(7)

Souvenir book. Featuring “Blindman’s Buff” by Barzaghi Francesco, and several cameos exhibited by Starr & Marcus, including one, mounted on a Roman cross and inset with diamonds, reproducing the central portion of Murillo’s “Immaculate Conception.” The Illustrated Catalogue and History of the Centennial Exhibition, Philadelphia, part 4. Published by John Filmer, New York, 1876. Exhibitions Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(8)

Russian icon. Given to Henry Knox Sherrill at his consecration by Bishop of Massachusetts, 1930. Sherrill Family Papers, Special Collections, Yale University Divinity School Library.

(9)

Pendant. Carved of mother of pearl with painted Madonna and child. Sherrill Family Papers, Special Collections, Yale Divinity School Library.

(10)

Ivory cross with blue and rose gems inlaid. Sherrill Family Papers, Special Collections, Yale University Divinity School Library.

(12)

Holy Cross from Alexis, Patriarch of Russia, 1956. Accompanied by card printed thus: “Alexis, Patriarch of Moscow and all Russia” and with handwritten note: “His Grace Bishop Henry Knox Sherrill; Please, accept this holy cross as a token of my cordially and brotherly love in Christ. 20 III 56.” Sherrill Family Papers, Special Collections, Yale University Divinity School Library.

(13)

Photograph. Cuban priest with large crucifix, ca. 1957-1959. Andrew St. George Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(Case 5c)

(22)

Chromolithograph. Ecclesiastical Metal work exhibited in Great London Exposition of 1862. Private Collection.

(21)

Bottle for Lourdes Water. Our Lady of Lourdes, French, ca. 1930. Private Collection.

(20)

Chromolithograph. Chancel organ exhibited in Great London Exposition of 1862. Private Collection.

(Case 5d)

(14)

Pamphlet. “Roman Peristyle in the Italian Village” and “Laughing Buddha in the Bendix Lama Temple.” Applied Photography, Oct. 1934. 1933-34 Century of Progress, Chicago World’s Fair. Photographs by Kaufmann & Fabry Co. Published by Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, N.Y. Century of Progress World’s Fair Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(15)

Fragment of lama’s robe from old Niya, n.d. Collected in 1905 in Chinese Turkestan by Ellsworth Huntington. Ellsworth Huntington Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(16)

Terracotta Buddha head, n.d. Collected in 1905 in Chinese Turkestan by Ellsworth Huntington. Ellsworth Huntington Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(17)

Painted plaster figure of a seated Buddha, from the lamasery at Khadaluck, prior to 300 A.D. Collected in 1905 in Chinese Turkestan by Ellsworth Huntington. Ellsworth Huntington Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(18)

Plaster Buddha (?) figure, n.d. Collected in 1905 in Chinese Turkestan by Ellsworth Huntington. Ellsworth Huntington Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(19)

Chalkware. The Powerful Hand, 2010. Private Collection.

Theme VI: Making Sense of Practice and Performance

Sensory experience pertains in multiple ways when individuals and groups engage in ritual, practice, and prayer. Many traditions instruct the negation of particular senses—closing the eyes or taking a body position (clasping the hands together, for example) that minimizes external distractions. Restraining one sense, however, can heighten others; and it is difficult to imagine a lived situation in which all of the senses might actually be “turned off.”

Not all objects, songs, or scents are engaged in the same way. Chinese Christian Hymns, a volume that contains “Confucian chants and old Chinese folk melodies ... captured for Christ,” shows sets of Christian words set to non-Christian tunes. Those who knew these songs as Chinese melodies would hear them with an added layer of familiarity while Christian missionaries from the West recognized the words but experienced the sounds as “foreign.” The same melody evoked a different feeling for individuals from different regions and countries.

Other sites of ritual, performance, and play invite sensory experience. Shrines and altars help situate sensory engagement in place, as music, incense, images, the light and warmth of candles, invitations for repeated touches, and directed movement through space manifest sensory and affective practices. In rituals of memorialization and memorization, sensory experience is often approached as a way to both remember and re-member. Beyond direct encounter, religious discourse also employs sensory metaphors to express more conceptual ideas. “Soul food” and the prompted imagining of consuming scripture shapes the type of radio program orchestrated by Evangelist Clinton White for example.

(Case 6a)

(1)

Lithograph. “Imperial Worship of Shangti on the Altar of Heaven at Peking (From a Chinese Painting).” From S. Wells Williams, The Middle Kingdom, unknown edition (mid-nineteenth century). Salisbury Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(4)

Advertisement. “Soul Food,” The Catacomb Press, n.d. (ca. 1970s). Published by Evangelist Clinton White, Lancaster, New Hampshire. Movement (Protest) Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(Case 6b)

(2)

Ephemera. Unknown pink and white illustration, Jerusalem, Israel, ca. 1980s. Christopher Phillips Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(3)

Musical program. Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, ca. 1980s. Christopher Phillips Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(6)

Photograph. Cuban Revolutionaries, ca. 1957-1959. Andrew St. George Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(7)

Photograph. Wedding at the National Cathedral (Havanna) of Fidel Castro’s sister, Emma Castro, April 1959. Andrew St. George Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(9)

Rosary made from rose petals, 20th century. Private Collection.

Theme VII: Making Sense of Space and Movement

While dominant twentieth-century theories of secularization might suggest that movement somehow only occurs progressively away from a seemingly stagnant or even backwardly moving, regressive “religion,” the objects in this section of the exhibition demonstrate the movements of religious bodies—corporeal and incorporated—in and through kinesthetic experiences situated in time and space.

In the context of Christianity, these experiences often denote worship within officially marked religious sites. But sense does not ‘turn on’ when one arrives in such locations; people bring their sensing bodies to spaces deemed both secular and sacred. This means that bodies moving in and through space engage with religious venues while becoming “religious” sites themselves, reshaping and being reshaped by such experiences.

Likewise, pilgrimage acts as a tool for worshippers, allowing access to holy sites and incorporating bodily experiences of movement. Movement also becomes more complicated or strenuous with distance. In addition, the environments of sacred sites are frequently designed to necessitate uncommon bodily experiences, such as moving the body underground. Alternatively, movement can be simplified to facilitate access to sacred objects. World’s Fairs brought objects from across the world into one space, so a visitor could experience them as a single new assemblage without having to travel to disparate locations. As the book designed to teach Talmud to young students further instructs, the built environment—symbolic and material—can both restrict and facilitate movement and communal engagement in space.

A body walking, dancing, kneeling, standing, sitting, or recumbent serves as a sensual interface in the porous and shifting relations of the sacred and secular. Experiences differ for one traveling by railway, compared to one traveling by somersault. Movement changes the sensed encounter with religious objects, familiar and foreign. Kinesthetic endeavors play significant roles in the creation or designation of “new religious movements” and their challenges to “progressive” notions of secularization.

(Case 7a)

(1)

Magazine essay. “A Slice of Heaven,” by Eugenie Gluckert. The Messenger, 1941. Essay describes the underground shrine to St. Anthony (destroyed by fire in 1960) in Oceanside, New York. Private Collection.

(2)

Journal entry. Richard Crary Morse, 8 Months in Europe, 1838. Morse Family Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(3)

Postcard (reproduction). “Listen to what I tell you ask not to see my face.” Printer unknown, undated. Paul Kagan Utopian Communities Collection, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

(4)

Postcard (reproduction). “It is through woman, that wonderful creature, that man is born into this world says Father Riker.” Printer unknown, undated. Paul Kagan Utopian Communities Collection, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

(5)

Manuscript pages. “Chorovods,” by P.D. Ouspensky, ca. 1930s. P.D. Ouspensky Memorial Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(6)

Photograph. P.D. Ouspensky in front of temple, India, ca. 1914-1927. P.D. Ouspensky Memorial Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(Case 7b)

(8)

Opening Day Program, cover page and text. “Dedication Service—Temple of Religion” New York World’s Fair, April 13, 1939. Century of Progress World’s Fair Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(9 & 12)

Souvenir book and rendering (reproduction). Bridging Two Worlds. New York World’s Fair, 1939-1940. Halls of the Jewish Palestine Pavilion. Ed. Frank Monaghan. Designed by Donald Deskey. Published by Exposition Publications, Inc. 1939. Century of Progress World’s Fair Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(10)

Instruction book. Hayim Parush, Perush hai: ‘al Masekhet ‘Eruvin. Jerusalem: H. Parush, ca. 1980s. Part of a series intended to help teach Talmud to young students through pictures. This book pertains to Tractate Eruvin, and concerns ways in which a group of homes can be symbolically transformed into one private home in order to allow Jews to carry things into and out of their homes on the Sabbath. Judaica Collection, Sterling Memorial Library.

(11)

Passover Haggadah. Maxwell House Coffees, General Foods Corporation, 1987. Private Collection.

(12)

Copper engraving (reproduction). Figure IV: Explanation of Sabbath Ceremonies. From Kirchliche Verfassung der heutigen deutschen Juden, by Johann Christoph Georg Bodenschatz. Published: Frankfurt and Leipzig, 1748-9. Top three rows show an 18th-century Christian audience how Jews can symbolically unify streets, courtyards and cities to allow Jews to carry things or travel between private and shared spaces on the Sabbath, activities otherwise forbidden. The bottom row depicts the Sabbath oven and a pot for cleansing Sabbath utensils. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

(Case 7c)

(13)

Railway poster (reproduction). “Siam, Beautiful Bangkok, The Jewel City of Asia,” n.d. Century of Progress World’s Fair Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(14)

Pamphlet. “The Pagoda. Twenty-five Chinese Songs,” compiled by Bliss Wiant, 1967. Donald MacInnis Papers, Special Collections, Yale University Divinity School Library.

(15)

Booklet. “Chinese Christian Hymns,” hymns by F. Olin and Esther B. Stockwell, 1941. Donald MacInnis Papers, Special Collections, Yale University Divinity School Library.

(Case 7d)

(16)

Hand-colored lithograph. “Sacred Tomb of the Blessed Redeemer,” Currier and Ives, ca. 1857-1872. Private Collection.

(17)

Photograph. Adult full immersion baptism, from The Oregonian newspaper, ca. 1960-1970. Note the River Jordan Mural behind the pool. Private Collection.

(18)

Photograph. First Holy Communion, ca. 1960. Private Collection.

(19)

Hand-colored lithograph. “Sacred Tomb of the Virgin,” Currier and Ives, ca. 1857-1872. Private Collection.

Theme VIII: Making Sense of the Extra-Sensory

Religious objects serve not only ritual and liturgical functions but also provide physical form to apparently extra-sensory ideas and experiences. The items in this section of the exhibition function as “case studies” of extra-sensory perception. In this context, these items are displayed together to provoke questions about how the senses are used to order what is allowed to take the name “religion” in the first place.

Extra-sensory experiences constitute the “evidence” of religious knowing in particular ways. At various times and in various places such experiences have been deemed spiritual or religious, or some combination thereof. The institutionalization of the five senses has achieved a legitimizing function for religious experiences even as empiricism has used sensory evidence to set up a dichotomy between science and religion.

The senses serve as a purveyor or conduit of information; often the extra-sensory joins heads and hands. Whether locating lumps on a skull, turning tarot cards, memorizing saints on one’s fingers, singing creation songs, or following the spiritual revelations of the Ouija board, religion has been shaped materially and ideationally through inter-sensory joinings. These inner abstractions are transformed into material products and practices. Importantly, as mind, body and spirit are rendered accessible, media technologies—from paper and pencils to playing cards—condition how people imagine the heavens, the ways they seek to commune with one another, and how the beyond speaks to those grounded within the earthly realm.

(Case 8a)

(2)

Newspaper advertisement. “Rev. Moon’s religious freedom: It’s yours, too.” Washington Post, July 14, 1977. The Unification Church, New York. Movement (Protest) Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(3)

Magazine cover. “Wartime Madonna,” The Messenger, 1941. Private Collection.

(4)

Fan. “Sunday Morning,” Mickey Funeral Service, New York, NY, ca. 1963. Private Collection.

(5)

Photograph (reproduction). National Farm Workers Association strikers march to Sacramento during California Grape Strike. 1966. Jon Lewis Photographs of the United Farm Workers Movement, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

(6)

Photograph (reproduction). National Farm Workers Association strikers arrive at state capitol on Easter Sunday. 1966. Jon Lewis Photographs of the United Farm Workers Movement, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

(Case 8b)

(7)

Newspaper article. “The Four Freedoms,” by Nicholas Murray Butler, New York Times, World’s Fair Section, March 5, 1939. Century of Progress World’s Fair Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(8)

Photograph from travel scrapbook. Initiation into Neptune’s realm (Military ritual), ca. 1917-1919. Albert Heman Ely, Jr. Papers. Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(1)

Photograph. Fidel Castro busts, 1961. Andrew St. George Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(9)

Fan. “These Americans Died for Freedom,” Ashley-Grigsby Mortuary, Los Angeles, CA, ca. 1968. Private Collection.

Theme IX: Making Sense of Public Life

Individuals and groups employ a robust human sensorium, in public as well as in private, as they attempt to make “sense” of everyday and extraordinary activities, rituals, and relations. Sensory engagements help constitute and control the “religious” and the “political.” To examine ostensibly political objects and images that take up and use the discursive practices and performances of the religious need not merely suggest the surreptitious use of religious metaphors in politics or vice versa. Together, the objects here call into question how artifacts, images, behaviors, and the very sensory practices of human lives are categorized.

The stakes in such distinctions are significant. It pays to attend to the ways individuals and groups produce and adjudicate such decisions in public life. In this context, some ways of doing and being are allowable in public while others are forbidden or foreclosed.

Some objects in this section of the exhibition invoke scenarios and repertoires frequently attributed to the religious, as in the images of “Neptune’s Realm,” an initiation ritual performed each time a sailor first crossed the equator. Employing practices attendant to particular sensual qualities—here the cooling touch of water as another gently guides one through submersion and ascent—creates sensorial equivalency with acts of Christian baptism. Other objects, like the photograph of plaster casts of Fidel Castro, pick up, reframe, and re-view the ambivalent imagery and positionality of religious and political leaders. Photographs of Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers depict laborers picking grapes and protesting with banners decorated with apparently religious imagery; these evoke the sensory qualities of physical work, public devotion, and civic engagement.

(Case 9a)

(1)

Phrenology Chart. Published by O.S. & L.N. Fowler with S. Kirkham, n.d. Chart to accompany “Phrenology Proved, Illustrated, and Applied” by O.S. Fowler. American Life Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(2)

Photostat copy. “Fludd’s description of perception,” early 20th century. P.D. Ouspensky Memorial Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(3)

Pamphlets. Synopsis of Phrenology; and the Phrenological Developments, Together with the Character and Talents of Olivio P. Bullard as Given by L.N. Fowler, Dec. 30, 1841. 20th Edition. Published by O.S. and L.N. Fowler, 1938. Synopsis of Phrenology; and the Phrenological Developments, Together with the Character and Talents of Mrs. Joseph P. Bullard as Given by [A.M. Ketason?], Jan. 19th, [1848?]. 175th Edition. Published by Fowler and Wells, 1847. Beecher Family Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(Case 9b)

(4)

Loose drawings for manuscript. De Musica Mundana & De Musica Anim., from The Fludd Opera, by P.D. Ouspensky, ca. 1930s. P.D. Ouspensky Memorial Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(5)

Photostat copy. “Lichtel’s Perfect Man,” ca. 1930s. P.D. Ouspensky Memorial Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(6)

Annotated Tarot Deck and Key to the Tarot Text, by Arthur E. Waite, 1936. P.D. Ouspensky Memorial Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(7)

Photograph (reproduction). Members of The Farm, an intentional community founded by Stephen Gaskin near Summertown, Tennessee. January 1976. Paul Kagan Photographs of Utopian Communities and Personal Papers, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

(8)

Photograph (reproduction). Members of The Farm, an intentional community founded by Stephen Gaskin near Summertown, Tennessee. January 1976. Paul Kagan Photographs of Utopian Communities and Personal Papers, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

(Case 9c)

(9)

Photograph. Jane Roberts at a book signing for The Seth Materials in Elmira, NY, n.d. (ca. 1970-71). Roberts began speaking to Seth in a trance in December 1963 and subsequently published several books based on her various sessions with him. Jane Roberts Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(10)

Musical score (photocopy). “The Story of Creation,” with lyrics in Sumari, Jane Roberts’s trance language, 1972. Transcribed from a tape by Wade Alexander. The song is also featured in chapter 15 of Roberts’ Adventures in Consciousness. Papers compiled by Robert F. Butts. Jane Roberts Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(11)

Playing cards. “Seth Says” playing cards with anecdotes and quotes from Jane Roberts’s various Seth books and accompanying book titles and page numbers. Joy Distributors, 2001. Jane Roberts Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(12)

Drawings (photocopy). Images of Seth, a personality encountered by Jane Roberts while in a trance or dissociated state in 1963. Sketches [top] by William Cameron Macdonnel. Portrait [bottom] by Robert Butts. n.d. (ca. 1960s). Photocopy and annotation by Robert F. Butts. Jane Roberts Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(13)

Notes (photocopy). “Jane and Judy at the Ouija Board.” Annotated copy of original notes taken during January 9, 1965 session. Communication with the spirit of Bob Fox—Born 1923, Died 1956. Papers compiled and annotated by Robert F. Butts. Jane Roberts Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(14)

Newspaper article. “Extra-Sensible Perception.” The New York Times, 1977. Brand Blanshard Papers. Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(18)

Sketch (photocopy). “My WYOMING,” with annotation by Roberts F. Butts. Sketch based on internal image seen by Butts in connection with voices heard while doing yoga exercises. March 28, 1965. Jane Roberts Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(Case 9d)

(15)

Poster (reproduction). Advertising lecture by Prem Rawat (reverentially referred to as Maharaj Ji) at the Divine Light Mission. 1972. Paul Kagan Photographs of Utopian Communities and Personal Papers, Yale Western Americana Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

(16)

Pamphlet. “Satguru Maharaj Ji, 15 Year Old Perfect Master,” Divine Light Centers in New England, Divine Light House, Bethany, Connecticut, n.d. (ca. 1972-3). Movement (Protest) Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(17)

Flier. “The Lord of the Universe Savior of ManKind Sat Guru MaHaraj-ji,” Divine Light Mission, Hartford, Connecticut. Attached is a note for an event featuring the Holy Mother of Guru Maharaj Ji (Prem Rawat), n.d. (ca. 1972-3). Movement (Protest) Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

Theme X: Making Sense of Religion in the Archives at Yale

In Making Sense of Religion in the Yale Archive, individual, subjective, and institutional understandings of what constitutes “religion” inflect every archival access point. Questions concerning the archive’s definition of “religion” and “the religious” surfaced repeatedly in this curatorial project. The archive includes some kinds of objects and leaves out many others. The body of available materials severely constrains the possibilities for exhibition. As curators of this exhibition, we were left asking: What responsibility do we—as curators, researchers, and exhibition viewers—have in interpreting the diverse objects from this archive, particularly when the body of available materials has already been culled by the idiosyncratic religious “sensibilities” of multiple separate collectors and donors who made sometimes contradictory choices about what to include or exclude in the production of knowledge. In this context it also bears mentioning the housing of these materials in a building architecturally indebted to traditional Christian forms. The collections thus risk reifying binary constructions of East and West, of (mostly Christian) religion and its investments in constituting its “others” (science, magic, the secular, superstition, and so on).

The objects in this case reflect the difficulty of representing a wide array of religious practices and beliefs when the archives from which one must draw materials problematically assert, at every turn, a Western, white, male, middle-to-upper class privilege. Indeed, even the ability and means to collect has relied on a particular socio-economic status. In the past, collections have yielded objects and images deemed worthy of retention, by a particular person in a distinct historical moment. For objects engaging the religious sensorium, the archives at Yale University often include items that represent the “other’s” religious practices as deviant or illegitimate. To visualize the “other’s” religion has often meant to capture it on film or in text as a way to underwrite Western notions of the category religion. From missions to early Orientalist studies to scientists intent on observing the minutiae of spiritualism and its attendant “proofs,” the collections at Yale University represent larger contests over the authenticity, legitimacy, and sensory evidence of religious belief and practice.

(Case 10a)

(1)

Postcard. “Sun Dance of the Ponca Indians, 101 Ranch,” no. 124, published by H.H. Clarke, Oklahoma City, 1908. Sent from Elmer [?] in Lindsberg, KS to Mrs. Alfred R. Page in Castleton, Vermont, 1911. Page Family Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(2)

Photograph. “The Meeting at Little Wolf’s,” (verso), n.d. Included in a collection of missionary photographs. Page Family Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(3)

Commemorative newsletter. Punahou Bulletin, Hawai’i, May 1966. Arthur Howe Jr. Papers. Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(4)

Letter. To Arthur Howe, Hampton Institute, from Priest-in-charge at St. Cyprian’s Episcopal Church in Hampton, requesting land for new facilities, ca. 1957-1959. Arthur Howe Jr. Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(5)

Souvenir book. “Group from the Egyptian Exhibit, Main Building.” Text at the bottom of the page includes statement that “religion was a pretty costly thing even a thousand years ago.” The Illustrated Catalogue and History of the Centennial Exhibition, Philadelphia, part 8, 1876. Published by John Filmer, New York. Exhibitions Collection, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(6)

Manuscript. “A New Chapter in Psychology,” by John Ferguson Weir, late 19th – early 20th century. John Ferguson Weir Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(10)

Scrapbook album. Various engravings of religious figures, including Leang-a-Fa, the “Chinese evangelist,” who was ordained by Robert Morrison, the first missionary to China, ca. 1840s. Salisbury Family Papers. Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(Case 10b)

(5)

Personal notes on Moral Rearmament movement (MRA), ca. 1938-1940s. The Moral Rearmament movement was a Christian, anti-Communist group that sought to revolutionize the world based on four principles: Absolute Honesty, Absolute Unselfishness, Absolute Purity, and Absolute Love. Albert Heman Ely, Jr. Papers. Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(7)

Conference program. “Conference on the Methods in Philosophy and the Sciences” (a symposium celebrating the centenary of the birth of William James to be held at the New School for Social Research), Sunday, November 23, 1941. Brand Blanshard Papers. Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(8)

Manuscript (copy). By George M. Beard, n.d. Beard lists his impressions of a study at Yale and questions the unconscious movement of a hand or arm when near a particular object as demonstrative of clairvoyance. Beard concludes that there is no evidence as to the veracity of this phenomenon in the study. George Miller Beard Papers, Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.

(9)

News dispatch. “Humanists, Alarmed by ‘Irrationalism,’ Sponsor Study of Paranormal Phenomena.” Religious News Service, Tuesday May 4, 1976. Brand Blanshard Papers. Sterling Memorial Library Manuscripts and Archives.