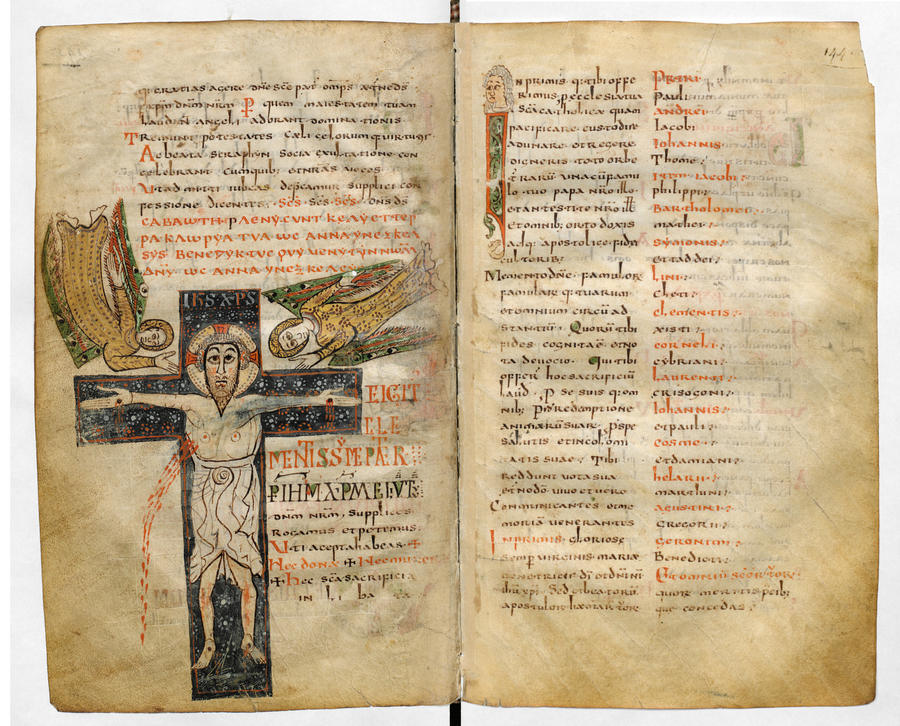

The image of Christ on the Cross, either as an element of a narrative scene (a Crucifixion) or as an isolated object of devotion (a Crucifix) is so common in the artistic and religious traditions of the last millennium of Western art, especially but not only in the Catholic tradition, that it is seldom recognized that such images are altogether absent during the first centuries of Christianity, and remain rare at least through the eighth century of the common era. One of the earliest surviving examples, from the closing years of that century and from the Frankish kingdom of Charlemagne, is the largest figural miniature in a richly decorated manuscript of the Sacramentary, the collection of mass and other liturgies, long preserved in the monastery of Gellone in southern France.

In the Gellone Sacramentary, Christ, wearing a white loin cloth, stares outward at the viewer, while blood spurts from the wounds in his hands and feet, and especially from his side. He is thus shown as if nailed to a cross, but this is no wooden cross and indeed no cross at all. It is colored deep blue, studded with white and red flower-like shapes suggesting stars, and indeed it actually is the letter T of the opening words of the Canon of the Mass, the consecration of bread and wine as the body and blood of Christ, in the Latin version here "Te igitur clementissime Pater . . rogamus" ("Therefore we beseech Thee, most merciful Father"). The body and blood so vividly displayed in the miniature are therefore not an "historical" but a directly liturgical image, representing and evoking not a past event but the present miracle about to be performed by the priest, who literally sees this image while reading the text to the gathered faithful.

The wide open, staring, eyes of Christ seem from a "narrative" point of view misleading or even wrong, for when his side was pierced with a lance, according to the only Gospel account of the event (John 19: 33-35), Christ was already dead. Here he seems very much alive, indeed powerful and vigorous, and the sense of lively movement is enhanced by the two golden figures descending from above. These are the seraphim, singing their hymn "Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus Dominus Deus Sabaoth. Pleni sunt caeli et terra gloria tua ..." (Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God of Hosts, Heaven and Earth are full with your Glory"), which immediately precedes the Canon in the liturgy, and which is here written between them in words singled out by their golden letters in capital rather than minuscule script, letters which in many cases are written using Greek letter forms although the text is actually in Latin. It is as if the Sanctus hymn is being sung by the seraphim along with the priest as he reads. Indeed the text immediately above the image on this page specifically states that the seraphim concelebrate with us, mixing their voices with ours (seraphyn socia exultatione concelebrant, cum quibus et nostras uoces). Everything is calculated to make the reader, the viewer, stop and attend most carefully to this special moment.

Never before had this initial been treated as a place for the appearance of the Crucified Christ; indeed, the historiated initial is a new genre appearing only in the eighth century. The reader of the Gellone Sacramentary can hardly fail to note the implications of this blue background, for this is the only place in the manuscript where the blue pigment appears! The blue cross refers to the notion that the sacrificed body of the crucified Christ is identical with his glorified body in heaven, where he sits by the throne of god. This notion is supported by the association with the Sanctus hymn, which derives from the vision of Isaiah (6:3) who "saw the Lord sitting upon a throne . . . [and] . . . upon it stood the seraphims. . . [who] . . . said: Holy, holy, holy, the Lord God of hosts, all the earth is full of his glory."

The figural initial P at the top left of fol. 144r, facing the Crucifix miniature, is associated with the word ecclesia and is logically if not conclusively identifiable with her (the text begins pro ecclesia tua sancta catholica). The figure is represented as a beardless long-haired youth or woman, and is consistent with images of the personified church. However, note that the John text for the Crucifixion, which provides the motif of the pierced side of Christ, specifically ends with "And he that saw it, hath given testimony; and his testimony is true. And he knoweth that he saith true; that you also may believe" (John 19: 35). If this text is associated with the initial in the viewer’s mind, it could mean that the figure would be interpreted as the witness "seeing" the crucified Christ, perhaps the spear-bearer Longinus, or more likely the Evangelist John, who specifically says in his Gospel that he was present, and since he tells the tale he is vouching for the veracity of his witnessing.

Other works of this period, during the reign of Charlemagne (768-814) dealt with the theological aspects of art works, and indeed there was a major controversy at this period immediately after the Seventh Ecumenical Council at Nicaea in 787 which approved the use of religious images by Christians for instruction and devotion, with the Franks, the papacy, and the eastern church expressing sharply differing positions. This image incorporates some of these intense concerns, making a theologically sophisticated and powerful work but restricting its viewership to the clergy, and linking it, making it in some measure subservient to, the divine liturgy and to scripture.